Today in America, we are trying to prepare students for a high tech world of constant change, but we are doing so by putting them through a school system designed in the early 20th Century that has not seen substantial change in 30 years. - Janet Napolitano

The only way you can invent tomorrow is if you break out of the enclosure that the school system has provided for you by the exams written by people who are trained in another generation. - Neil deGrasse Tyson

There's no end to the river of books written about the American Public School System (an Amazon search shows 5,233 results), and the federal studies would probably fill a Raiders of the Lost Ark-style warehouse (which as it so happens, actually resembles the Amazon warehouse). Few endeavors have been so thoroughly dissected by so many diverse groups of populations - politicians, parents, statisticians, philosophers, educators - just to name a very few. These research efforts all points to the fact that the American education system, including post secondary education, is a complex stew of politics, pedagogy (and andragogy), economics, and even architecture - our topic for today.

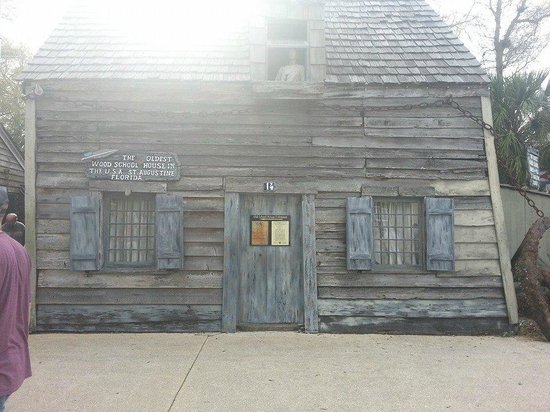

The mix becomes apparent when considering the history of American public education. In the early days, no one worried about learning-specific architecture - it was just whatever structure was handy. Houses, churches - whatever was large enough to seat a dozen students or so. If one ever visits the country's first school house in St. Augustine, some of the first thoughts are, "this is really small", and "this must have been very depressing":

|

I always imagined the woman at the upper window dropping a note that says, "get a ladder and get me out of here."

|

|

| Don't know your letters? You get to practice all by yourself in Harry Potter's cupboard under the stairs! |

Religious instruction, math, and grammar made up most of the early curriculum, and there was no real concern about the comfort of the students. It was learning by rote memorization - wisdom passed down by the teacher to the students all sitting in rows for hours.

While private education was primarily for the elite, public education was informal and took place in the home or church, where its primary purpose was to teach children a trade or skill (tanner & Lackney, 2005). These educational experiences encouraged children to pursue activities that prepared them to practice acquired technical skills. Whether learning occurred at home or in the church, formal education was characterized by the study of the Bible, which entailed memorizing many of its passages (Bissell, 1995). Learning occurred through rote activities in which student acquired information about the Bible, rather than gaining knowledge by sharing and resolving divergent interpretations of the text (Lippman, pg. 75).

As Lindsay Baker states in a National Clearinghouse for Educational Facilities report, not a whole lot changed, other than the number of students, as towns and communities grew into cities, and the post-Civil War Industrial Revolution dropped into high gear. And really, why would it? Teaching by rote seemed to bear fruit - most students could pass the exams connected to the material that was being taught, so the assumption was this teaching method was working. Why not simply apply it to a larger scale. So soon the schools themselves began to resemble the factories the children were destined to head into in shockingly short order:

|

| Welcome to the factory, er, school - Stowe School in Wynadotte County, Kansas, circa 1890. |

|

| Okay ladies and gentlemen of the of the 1899 Washington, DC school system - who's pumped up for learning?! |

Progressive education reformer John Dewey and others near the turn of the 19th-20th centuries took a look around at the dreary state of American education and advocated changes that would bring forward thinking pedagogical changes to the curriculum.

But... towns, cities and states were already heavily invested in the school buildings they had built, so while Dewey's, and others, ideas might be full of merit, they would have to fit into pre-existing school designs. And the marriage wasn't completely harmonious:

While teachers' and students' desks were unbolted from the floor and science laboratories were designed so that students could conduct their own experiments (Bissell, 1995), students' furniture continued to be arranged in rows facing the teacher at the head of the room. The ideology of flexible, active learning was merely a pretense for integrating an educational system for "teaching specific people to move into proper societal position" (Rivlin & Wolfe, 1985). Even though Deweyan principles appeared to be institutionalized architecturally, they were limited (Lippman, pg. 81).

It doesn't take an expert to see that the architecture and pedagogy of the time did sort of match - it was all about student control and being teacher-centered - not necessarily learning-centered.

Those concepts wouldn't come along until nearer the end of the 20th century, not until (not coincidentally), the rapid development of computers resulted in better tools for the statistical measurement of learning (Zenisky & Sireci). It was then much of the measurement of academic achievement shifted away, at least in part, from compiling data on short term, just-get-through-the-test- kind of learning retention, and toward tracking long-term learning retention through sophisticated longitudinal studies.

And the results weren't pretty (Fink, pg. 2).

These sort of findings brought a ratcheting up of the pressure all along the political and academic spectrum for schools generate better quantifiable numbers. That in turn created an environment that allowed for the research into different models of learning, resulting in... tomorrow's entry, focusing on how new pedagogies are pushing new school architecture and classroom designs.

References:

Baker, Lindsay. (2012). A History of School Design and its Indoor Environmental Standards, 1900 to Today. Washington, DC: National Clearinghouse for Educational Facilities.

Fink, L. (2003). Creating significant learning experiences : an integrated approach to designing college courses / L. Dee Fink. San Francisco, Calif. : Jossey-Bass, c2003.

Lippman, P. C. (2010). Evidence-Based Design of Elementary and Secondary Schools [electronic resource] : A Responsive Approach to Creating Learning Environments. Hoboken : John Wiley & Sons, Inc., 2010.

Zenisky, A. L., & Sireci, S. G. (2002). Technological Innovations in Large-Scale Assessment. Applied Measurement In Education, 15(4), 337-362.

No comments:

Post a Comment